The production of creative works by artificial intelligence (AI) provokes many responses—philosophical, cultural, economic, and legal. I have already argued against copyright protection for works created by AI, supporting the longstanding doctrine that copyright rights can only attach to works of human authorship. But one paragraph in a recent article by attorney Adam Adler raises a potentially difficult question as to whether human prompts directing an AI to produce work could ever constitute authorship of the resulting work? Adler writes:

… proponents of AI art don’t have to look very hard to find the required creative contribution. The most prominent AI works are generated through trial and error using specially crafted word prompts. For example, Jason Allen, the winner of the Colorado State Fair, spent 80 hours crafting the prompts he used to generate the art and tested over 900 different prompts before settling on the winner. Given the sensitivity of AI art generators, one could argue that the selection and refinement of prompts (at least as they are used today) involves significant creative work, analogous to placing a camera or framing a shot. And because a human’s prompt selection informs the creation of the entire work, there would not be any obvious way to disentangle the creative and non-creative elements of the work

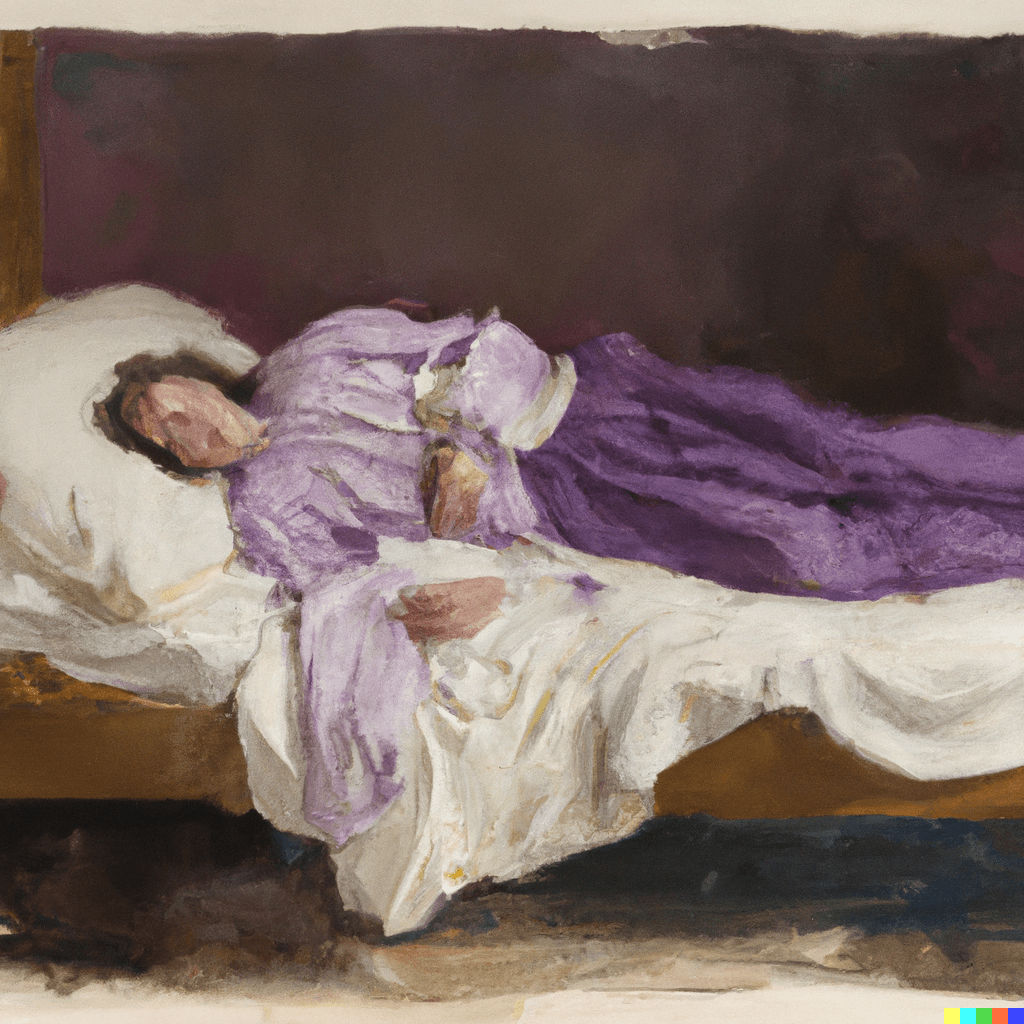

Whether Adler endorses the view that the prompts in this example should vest James Allen with the rights of authorship in the resulting image, he is probably correct that advocates for copyrightability of AI works will advance this argument. But is the position valid? If I ask a friend to paint a picture of a weeping willow by a brook, my broad description does not constitute even joint authorship in the painting, and that example is arguably no different than my recent playing around with DALL-E 2 writing prompts with an existing painting in mind—Henry Wallis’s “Chatterton” (1856).

Although the results were nothing like the original work (and I am admittedly a novice propter), the image on the left could, eerily enough, be passed off by a would-be forger as an early sketch in the development of the Wallis painting, and it was admittedly astounding to watch these, and other variations appear in a matter of seconds.

But returning to the theme of this post, I maintain that I did not author these images or the other variations output by DALL-E 2. Authorship flows from the creative choices made by a human, and there would need to be a colorable nexus between my prompt writing and the selection and arrangement of the choices made in the work—in this case a visual work—upon its fixation.

Prompts by themselves may be protectable “literary works” under copyright law—not unlike computer code, which can be sufficiently creative while also serving a utilitarian function as a set of instructions. But the potential copyrightability of prompts themselves does not necessarily extend to protection of the resulting work—not even in the case of Allen writing complex prompts into the app Midjourney to produce the visual work he called “Théâtre D’opéra Spatial.”

Neither the 80 hours Allen spent nor the 900 different prompts he tested has any bearing on a potential claim of authorship in the resulting image because copyright does not protect “sweat of the brow.” Copyright also does not protect ideas or concepts; and the incident of copyrightability is agnostic with regard to the author’s intent, message, or methodology. Unless there is a lack (i.e., less than a modicum) of originality in the work, copyright attaches upon fixation, and without consideration as to how or why the work was made. But the Allen example implies a potential difficulty in the doctrine to which Adler alludes in his description.

Given the time and energy Allen spent on the prompts, we can assume he developed a somewhat complex set of instructions, and it is conceivable that there may be a point at which a creative arrangement of prompts could approach a defensible claim of human authorship in the resulting work output by the AI. But it’s tricky, and I am skeptical.

Ordinarily, the moment a work is fixed in a tangible medium, the human’s creative choices may be inferred, credited solely to the human, and the choices need not be explained. In the photojournalist’s image of the factual event, it is longstanding doctrine that the existence of the image itself is evidence that she made sufficient choices (even in a second or two) to meet the “modicum of originality” threshold, and copyright rights are vested in her without asking her to describe or defend the choices made.

AI production may frustrate this doctrine in the near future by providing a reason to ask how a vast amount of work has been produced and about the nature of the human involvement in its production. Then, even if prompts may be protectable literary works on their own, the consideration as to whether this confers authorship to the human in, for instance, a resulting visual work or music work output by the AI implies a case-by-case consideration of copyrightability that would be administrative chaos for the Copyright Office.

It is hard to imagine a generally applicable doctrine that would harmonize the human authorship requirement with a definable nexus between prompt writing and the resulting work, and this suggests that the law must hold that copyright does not attach where an AI has made any (and likely most) of the creative “choices” in the work being claimed.

This view is consistent with the purpose of art and the purpose of copyright—both of which are profoundly human constructs. Neither copyright’s utilitarian origins (i.e., the author must earn a living), nor its civil rights origins (i.e., the product of the author’s mind is naturally his property) has any meaning whatsoever to a machine, just as machine made “art,” in my view, will ultimately mean nothing to humans.

Art without human creators may be decorative, interesting to a point, useful, entertaining, or even conducive to computer science in other contexts, but the products themselves are bloodless in every sense. Making art and engaging with art is one of the most human of all activities—transcendent and spiritual for many—and I have no idea why it would ever be outsourced to computers. One might as well suggest that the Buddhist set his mobile device in front of the alter to chant for him while he does something else with his body, mind, and hands.

When Henry Wallis revealed “Chatterton” at the Royal Academy in 1856, it caused a stir—both because it was considered a masterwork made early in the painter’s career, and because its romantic yet grim subject matter was viewed by many as a comment on the poor treatment of artists. Chatterton’s suicide by arsenic at the age of seventeen was believed to be at least partly the result of his abject poverty due to the failure of publishers to pay him for his writing. His “Last Verses,” found with his lifeless body, contain an 18th century version of the artist who was supposed to live on “exposure” rather than compensation.

Farewell Bristolia's dingy piles of brick, Lovers of Mammon, worshippers of trick! You spurned the boy who gave you antique lays, And paid for learning with your empty praise.

Two and a half centuries later, “Lovers of Mammon” have invested billions in technologies and business models designed to devalue creative work and infringe copyright rights at massive scale. And now, we enter the next phase, when machines are being “trained” on volumes of human-authored works to potentially replace humans in the production of literary works, visual arts, music, and perhaps eventually, performing arts. And, as usual, the technology is advancing apace without any consideration as to whether it can reasonably be called progress.

Illustration by: zdeneksasek

I don’t think it will become copyrightable images for several reasons that seem to be missed by many.

First, short phrases are not copyrightable in the current code. OK, that could be argued, but as of today, to me, prompts are just short phrases.

But second, and this is more complex, is the fact that the same prompts to different AI image computers will produce very different results. The final output is determined by the computer, not the prompt writer. And several variations are produced.

That is no different than an art director giving me a layout, a sketch or more, and detailed instructions for casting, wardrobe, background, props, etc., to produce a photo for an ad. Ad agencies have tried, and always failed, to claim co-authorship for the copyright. The same layout to different photographers yield different results, so the authorship lies with the photographer.

As this get hashed out in the future, I’ll continue to use AI, with my own photos and artwork as a seed, and prompts which I increasingly keep private, to work out ideas and just for amusement.

IMO it’s an art form as long as significant original thought and effort went into it, and any seed photos were the artist’s own, not something belonging to someone else. When users use other artists’ names as a prompt, it’s less their own work, less original.

Great that AI gave people a tool to stretch their imaginations and even create art without even having any art skills. Those are all positives, and it doesn’t scare me that “regular people” can make art now. As with all artwork, originality should matter, and sadly, people have managed to use this marvelous tool to do the same old unoriginal crap, using photos they stole off google and other artist’s names as prompts, (especially artists who are still living, yikes).

The bar for originality is low, for copyright registration, already. I suspect if you looked at the effort and creativity, plus original seed photos, it would be easier to see how an AI image could have taken more original thought and imagination than some very simple cartoons, etc.

At one time photography was not thought to be original or protectable, either, because it is “just pushing a button.” We know that to be untrue. AI will eventually be treated the same as other visual art forms, but as with all of those media, too, it’ll have to meet at least the low bar of originality. Typing in some living artist’s name and using a photo from a google search should not cut it. Proving how you got the AI image will be a harder nut to crack, especially if the AI program does not keep the whole process in its memory so you can show it.

That said, I am not technically all that savvy, so if I called something by the wrong name, sorry.